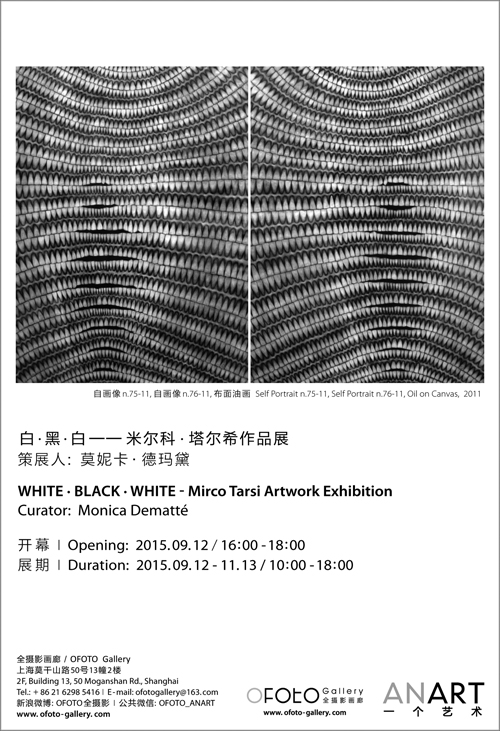

- WHITE · BLACK · WHITE

- Artist: Mirco Tarsi

- Critic: Curator: Monica Dematté

- Opening: 2015.09.12 / 16:00

- Duration: 2015.09.12 - 2015.11.13 / 10:00 - 18:00

- Address: ANART. 2F, Bldg.13, 50 Moganshan Rd., Shanghai, China

White, Black, White

by Monica Dematté

Re-elaborated version of a conversation with Mirco Tarsi held in Jesi on 13th February 2015, as well as of fragments of texts and life

For several years Mirco has been living in an ancient rented flat in the city centre of Jesi of which he takes great care. The ceilings are frescoed with odd figures, which he adds to by displaying works of art (mostly by others) and creatively-designed objects, lining up books on the floor with a studied negligence, building a routine of many little rites directed to make the fatigue of living more acceptable. Mirco considers himself a flexible, benevolent person, and puts strategies in use to keep at bay the anxiety he feels or he thinks he feels, indulging in endless cigarettes and glasses of wine voluptuously savoured. Mirco thinks he does not have new ideas and has nothing to tell, but when asked questions, he replies gladly, extensively, with a slightly alexandrine but fully heart-felt language. He pretends to be a snob but he is shy rather than arrogant, hiding his fair and good-natured eyes under the short brim of a small hat he wears in all seasons. He loves sleeping in but he often has to get up at hours before dawn to go and work as a janitor in the archaeological museum of a village in the Marche region, a job he dislikes but which has allowed him to get by and devote himself to painting his biggest passion since childhood.

Of teeth, he would prefer not to speak. Having painted them for fifteen years he feels that should be enough. To him it is the work of art that should communicate, the viewers should take their time and pay attention to the work they are looking at. But Mirco also realizes that viewers, influenced by the visual result of their experiences and reflections, sometimes feel the need to understand his works better through verbal communication.

* M.D. Would you like to tell us about the origin of the iconography of the teeth, to which you have been dedicating yourself in a single minded and obsessive manner for many years?

M.T. I usually make a very articulate and introspective speech, combined with the art and its history. Now I can say the reason that drove me to identify the tooth – teeth – as my key motif, my personal cipher, is the result of a reconstruction of my past, a reflection that through my intuition passes from the history of art to the critique, it is the repetition of a theme, of a pattern that proposes in pictorial terms the reiteration that characterises life.

First of all I will say that since I was small I have always had a great passion for both drawing and painting. It was my way to communicate, a way to adhere to reality. Through these expressive means I would make up for the lack of other abilities. My approach to the art world was spontaneous and naïf, for a long time I was self-taught, not owning the theoretical tools to be actually aware of what I was doing and why. Feeling that it wasn’t enough, only after my twenties was I able to focus on studies aimed at critically deepening the painting skills I had already long been practicing.

Then I realized that I had to confront the fundamental problem of having nothing to tell about my banal routine, which however was and still is my main reference. Through this introspective interrogation I began to wonder about the nature of art, and in that moment Filiberto Menna’s text “The analytic line of modern art”, which I studied carefully, became an essential reference for my work. In it the author distinguishes between modern and contemporary art, the fact that today’s works of art tend to lose their traditional expressive or representative - iconic - meanings to assume increasingly an abstract and conventional value of linguistic research, in these years when the practice of art constantly theorises on itself. My figurative approach has weakened bit by bit, and I felt encouraged to abandon the narration of the reality that I had previouslyperceived as the only possible way.

* M.D. I imagine that at the beginning of your path, above all, you took inspiration and nourishment from the history of art. Who are the artists you love or you have loved the most? Your reference points?

M.T. I am fascinated by strong works, fully felt, sewn on the skin. Francis Bacon and Giacometti are my mythical, unparalleled masters. Studying at the Academy of Fine Arts I discovered I had an approach and a manual skill similar to theirs; I literally wanted to be them. I suffered for a long time, then I understood that I had to stop envying them and go further because I don’t have new ideas and because everything has already been said and done. I really liked Bacon’s paintings from the Fifties, with their dark backgrounds, the open shouting mouths and the teeth. At that time I couldn’t quite understand why they engaged me, it was above all a very strong feeling. After indulging on Bacon for too long, one day when I was painting a head inspired by an Inca mummy, with open mouth and teeth well in view, I had a sort of intuition where everything was set in place in a perfect tangle of significance and significant. I sensed that those teeth that were obsessing me so much would have to expand onto the whole surface of the canvas and that everything else was unnecessary. Through the repetition of the tooth on the entire space – limited only by thedimension of the canvas – I moved from ‘representation’ to ‘presentation’, and ‘narration’ stopped to be my concern.

Since then my portraits have become serial, repetitive, based on that obsessive element that characterizes me. They have the value of a rite, they propose again and again the cyclic nature of life, like a visual mantra. I lingered on the tooth because it’s a dual and ambiguous element, symbolic of defense and attack, aggressiveness and smile, sensuality and instrument of nourishment. Later I tried to do other anatomic parts in order to avoid boredom, but they immediately looked didactic to me. At the cost of sacrificing the most pleasant, most spontaneous, less systematic aspect of painting, I chose repetition: a time that is mine but also everybody’s. I don’t actually do anything but reproduce what I see: my teeth in reiterated lines are a sort of chronicle of the reality of my time. We live in a time when human beings have lost themselves in the material world, in the fear of mortality that I myself have been obsessed by since the age of four.

Since I started to look inside myself I have understood that in art it is more important to be ‘creator’ than creative (quoting the Italian critic Bonito Oliva), and in that respect to have created a strong image is all Ineeded. Beginning with the first canvas covered with teeth I engaged myself in a unique work of art constantly changing. Initially, when I realized that I would repeat myself forever, I got scared, exactly like Roman Opalka in the ultimate decision of reciting his mantra to the end. Keith Haring’s diaries helped me a lot: I appreciated the strength and enthusiasm in his determination to cover the world with his personal iconography that in some works recalls a texture, a bit like mine.

* M.D. When teeth became your ‘cipher’, or even better your ‘self-portrait’, and you have conceived the idea to use them as a motif that represented you and to repeat it endlessly, did you ask yourself how they could evolve in relation to the progress of your life?

M.T. The very fact of being easily recognisable, the economy of the image and of the means to produce it, are to me like a protective shield. Just like any defensive attitude it may contain aggressive tones – some viewer perceives it and feels bothered – and here we go back to the issue of the ambivalence of the tooth where everything starts. Protected in my niche like an observer, I can take the liberty through reiteration to experiment with the concept of evolution. I go on adjusting the target in the formal composition of the general implant and in the execution of each single tooth, so that every little passage is a step forward where something is gained and something else is lost. When you look at them carefully, my paintings are all surprisingly different one from the other. My work has solid grounds but it is in a continuous metamorphosis through which I try to understand what I have done, learning from experience. At the present time I strongly believe there is a need of being fully aware of one’s own work. If in the past I thought it was acceptable and even in some ways desirable for an artist to ignore the origin of her/his works, to let oneself be guided by one’s own talent, in a vital way, nowadays I believe the author should be fully responsible for his actions. Certainly, this attitude sacrifices a lot of the spontaneity and enjoyment aspect of working within the ‘freedom’ human beingsare inclined to, and that has its price.

* M.D. Are you saying that now you no longer feel pleasure when working?

M.T. Yes, indeed, while I am painting I definitely do not amuse myself: the whole process is tiring, also physically, but I hang in there for the result. I am aware that if I wanted to paint for the fun of it, I wouldn’t achieve what I am looking for, so I’d rather enjoy myself in daily life instead. I gave up fun when painting because it didn’t belong to me. When I work seriously on a canvas I take a few days off my permanent job and paint restlessly, lingering on a canvas for 10 to 14 hours a day. At the end I am physically exhausted, even my bones ache.

* M.D. For the last few years – about seven, I believe – you have no longer used the brush, but pieces of toilet paper that you employ to remove the black colour with which you cover the former white surface of the canvas. The resulting white teeth are therefore the outcome of a subtraction of colour instead of a superimposition. What do you call this very peculiar operation?

M.T. I still call it painting. The push to this change initially arises from a practical need for a conceptual aspect that my work required. My paintings work well in big sizes. But with a traditional seventeenth century painting technique, made of drafts, afterthoughts and veiling like the one I practiced at the beginning, it would have taken me a very long time to accomplish a big canvas. My other concern is that the result, excessively heavy and chromatically redundant, lacked effectiveness: what I had inside wouldn’t come out in a satisfying manner. This happened everytime I lingered withthe brush and its pleasantness, or rather its tradition. And yet I still now find myself nostalgic, I don’t have any certainty and doubt constantly accompanies me, but the direction I have taken seems right.

* M.D. At the beginning your teeth were in full colour, repetitive but realistic. Then what happened? How was the passage from the brush and colour painting to the subtraction in black and white?

M.T. Just like for the genesis of this research, it was a sudden intuition in which everything assumed its right position, the black and white, the absence and the presence, it all wedged in a stratified sequence of dichotomies that would finally make my vision concrete. It happened during one of my depressive crisis. It was as if I had unloaded a burden. Giving up colours and brushes I also let go a large part of my disquiet. Pondering about it today, I don’t see how that colour could help, a colour which wouldn’t match with what I had in my mind, and which, I thought, wouldn’t even caress the eye. And after all I am partially colour-blind.

* M.D. How do you consider the black and white in relation with the other colours and to each other?

M.T. I consider the colour black as the sum of all colours and white as their absence. If you try to mix the three primary colours you will get the black. There are different theories about colours, like Newton’s, Goethe’s, Steiner’s. Painting canvases remind youof the concrete reality of human beings, I adopt a material perspective, as colours are made of pigments. Art manifests itself within the domain of the material but finds its place in the categories of the spirit, and there things are different. Still, a painting is a painting, it’s made of material substance, and without it the spirit cannot manifest itself.

* M.D. Black and white are two chromatic oppositions used among others in the symbol of the yin and yang, which you often refer to...

M.T. Yes, it’s about the dichotomy that in an anti-Manichaean vision builds up the whole reality. Without evil there is no good, without the dark there is no light and so on, the ancient eastern cultures understood this right. Perhaps it’s not so well-known that the yin and the yang also implicated in IT development, which makes us so proud and has its roots in the binary calculation where you shift from presence to absence, from white to black. The functioning of a computer, an extremely complex tool that is entering every single aspect of our life, starts from the so called bit, a unit of measure of information, constituted by 0 and 1, according to the binary logic.

* M.D. Do you think this opposition so poignant in meaning, so culturally and visibly strong, might have made your work more complete?

M.T. Nothing is ever complete in life.

* M.D. Fortunately!

I have noticed that in the past years you have been carrying out a more and more evident simplification, besides the chromatic one, how do you explain that?

M.T. Yes, this is very evident in my latest productions. During the execution of each single unit – in my case, a tooth – its heterogeneity is lost to the benefit of a richer composition as a whole, and this comes from the exhausting exercise of the repetition of an element. This is an aspect I am working on. In an evolutionary process it is natural that when something is gained, something else may be left behind, only to be retrieved in the next phase. You can understand this well when approaching Rudolf Steiner’s work which I have recently found extremely interesting.

* M.D. Perhaps the risk is to becomedecorative?

M.T. I don’t see it as a risk, but as a necessary passage, my‘rage’is still the same. After all the decorative aspect is important too, there is no need to make unpleasant paintings. Decoration is a problem when it becomes an aim. I don’t purposely want to avoid painting beautiful works. We all seek beauty, and I find it in my ruins.

* M.D. And where does this anger, this rage you are referring to, come from?

M.T. I don’t know. I have always been working on it. We should engage in a longer conversation but I would need much more time and awareness. And perhaps a psychoanalyst.

* M.D. Do you feel it is always at the same level?

M.T. The anger is there. Even if I can manage it better lately, it only needs to be stimulated to come out.

* M.D. Towards whom?

M.T. You know, anger is generated by frustration. To be honest, maybe I should turn this anger towards myself, because in each of us there is the whole cosmos, but it is not easy. It is easier to blame always something different from you.

* M.D. Let’s talk a bit about the ready-made objects on which you sometimes paint: how do you choose them?

M.T. I don’t really have rules, you know, I’m not very systematic, I let myself go. It is here that I allow myself the freedom of movement that in the painting practice I see as a danger. These two aspects together give strength to my research. At times an object hits me for its shape, some other times I’m intrigued by artifacts coming from other cultures. When I paint on them it is as if I was applying a primeval skin, it is a gesture of appropriation, just like the elephant eaten by the boa in Saint-Exupéry’s Little Prince, as Maurizio Giuffredi wrote, who was of amazing help during my growth. To that purpose I must say that my whole work is a self-portrait –the main theme from which my search has kicked off since its figurative beginning – and that the signature on each piece indicates its title as well. The signature is not my name but an acronym with an A., followed by the serial number of the piece of work and the year of its execution, everything set inside a xylography representing the snake that bites its own tail, the so called ouroboros. Since 2014 I have decided to remove the A. of autoritratto (self-portrait in Italian), my works have lost the title in the true sense of the word. They are not ‘untitled’, but only carry the number and the year of execution. Opalka once again.

* M.D. And then there are the sculptures you make yourself in clay, to cover afterwards with paint.

M.T. I have a strong relationship with sculpture, I consider myself a sculptor who has always been viscerally in love with painting. These two things combined work well.

* M.D. I am curious to know how you work: before you start painting a big painting, do you make a drawing, a draft?

M.T. Here again I don’t have any rules. Let’s start from the premise that the work begins as subtraction of fresh colour from a uniform layer, black, on which it is not possible for any preparatory intervention. At times on the white canvas, before applying the black, I trace a few lines with the charcoal to create a structure, but it is possible to have a completely different result at the end. Some other times I only imagine this structure. Lately I have also made small scale sketches with a very complex structure, as a memo to keep next to the canvas. When I work, I continuously adjust my aim. It might happen that I let myself get inspired by symbolic images of different provenance, of which I eventually forget the origin due to my bad memory, in this case too I prepare a draft of lines on a small sheet of paper to catch an idea I might achieve in the future.

* M.D. When you look at your paintings what makes you understand if a piece is good or not? Is your evaluation connected to the mood they evoke or to an aesthetic evaluation?

M.T. It’s an aesthetic evaluation. The work has to function formally and that’s it, there can’t be any other kinds of justifications. Content and form are two inseparable aspects, but in the end a painting or a sculpture is form, appearance, and if the form is not good then something has gone wrong.

* M.D. Have you ever wondered why your paintings are loved by the people who love them? I am asking this because your theories are not so visible in your works, and the viewers are mainly unaware of how much work and thought there are behind them.

M.T. This makes me truly happy. Not even looking at Cézanne’s paintings were viewers aware of his vision and anguish. If this happens, it means that I succeeded in my attempt to transfer content. Even if the form is appreciated beyond its content, the latter becomes a reality that settles.

* M.D. I think your theorisation is not the most important thing, it is your artistic sensibility that has driven you to do all this. I reckon you are more intuitive than rational. I actually like to ask you questions, to listen to you, in order to understand who you are, not to learn about how your works are created. With them I establish a visual, aesthetic, direct relationship. And anyway the art language goes well beyond and before all the theorisations, it is not verbally expressible.

M.T. Indeed. Theory is clearly built on the experience. I don’t like to talk about my work. I would always talk about something else. But in this historical moment I believe artists should reconsider the need to be fully aware of their activity, and to be able to theorize about it. Manymasters from the past did that, their works of art were almost maps of a certain content, just think about Leonardo or Michelangelo.

* M.D. So you give artists an important role. But what can they do in your opinion?

M.T. Artists have a very important role and they have a responsibility in what they leave behind to the viewers. Of course you can’t naively think that on a material level artists hold power, especially in the historical context. But they have to do at least one thing; that is to enrich the world through their production, creating the premises for people to reach a deeper awareness. Essentially, just like it happens in every field of human knowledge, artists have to do their job to their best, improving first of all their inner world. Artists create ‘reality’, they should not simply pursue mundane interests like power or money.

* M.D. What does it mean “to do your job well”?

M.T. To create significant meaning.

* M.D. What does the meaning, the content, correspond to?

M.T. To a vision.

* M.D. A heart-felt vision? A truth?

M.T. No truth exists, neither mine nor any others. We start from here. Just think of an artist like Jeff Koons, one of those I hate the most, he does have a vision of his own. It is not a vision aimed at enriching the world, as I see it, but that takes advantage of it. I don’t like his vision at all, nor do I like his works form an aesthetic point of view. Intellectually he is an enemy but he does his work well, he is a great professional and his work is very effective, otherwise I wouldn’t be here talking about him. The problem arises if, going on nourishing the idea of Celebrity, which has nothing to do with art, it becomes the one and only successful reference model, standing out and excluding every other way of expression and of thought that cannot make that much money run. Behind his works there is nothing else than a model of a social climber and winner, imbued with bad taste. When I think of Leonardo’s Virginof the Rocks and I compare it to one of Koons’ gadgets, it gives me the shivers down my spine. The worst part is that such a mindset penetrates the whole reality to the very bottom. When observing the collection’ s policies applied by museums, from the most famous ones to the most suburban, dealing with contemporary art and showing their interest towards artists of my generation, I can’t expect my works to be taken into consideration because my prices say that I am nobody. People prefer spending ten or a hundred times more because the courage to carry on a true research is missing. In private collecting things don’t go any better. The work of art is but a pretext. So “long live Koons and Celebrity” – I have nothing against them, rather against this big mass circus of contemporary art, which has abdicated from its critical attitude, from freedom and maybe also from dignity. The time when Rudolf Steiner used to theorise his reforming idea of the social triple articulation, maintaining the separation between cultural, juridical and economic lives, is well behind. As is, sadly, the time when the forward-looking entrepreneur Adriano Olivetti, strong admirer of Steiner’s work, showed to the whole world that this dream was indeed possible and desirable. A dream that fell apart with his passing away.

* M.D. Right. But there are places like the Mo Art Space where we actually think differently, and I hope that both you and other artists will take that into consideration, I wish this can give you at least a bit of hope.

Anyway, if somebody asked you what would you like to do in the future?

M.T. The artist.

* M.D. Do you mean a full-time artist?

M.T. Yes, to live off what I can do best without having to sign another contract of dependence to the reality of surviving, to be able to really ‘give back’ something. I am not saying that this would free me from all my existentialist drifts. But I know that when I paint for fifteen consecutive hours, even exhausted, in the evening I feel I have honoured the sense of life. Lots of real professionals, by the way, work at the same pace. Once I have completed my work after such an effort, if the result is really good, it is a real joy. Perhaps my anger comes from the fact that I have never had enough courage to really question myself. I sometimes think that I shouldn’t have looked for a job with a regular salary, to preserve the freedom of my work, that I should have plunged myself instead into life and see what would have come out. It can also mean death.

But in the end my work is the result of my experience and my decisions. Behind my painting there is my routine too, my punching the time-card.

If on the one hand the act of repeating is a symbolic expression of defense (mental and physical at the same time), on the other hand it is also a Zen practice, an attempt, as Tarsi himself says, to “reach the absolute zero, where rationality gives in to the unknown”. (Maurizio Giuffredi, 2004)

Vigolo Vattaro, 21st February 2015

Translated by Azania Dematté

Thanks to Christopher Taylor

Translated by Azania Dematté

Thanks to Christopher Taylor